|

Number 4. July 2016: 'Vauxhall Bridge', by J.C. Varrall.

|

|

|

|

fig.1. Vauxhall Bridge byJohn Charles Varrall (1794-1855) |

| This month's object may, at first glance, look rather uninteresting - apparently no more than a standard topographical view of a Thames bridge. The designer and engraver John Charles Varrall (1794-1855) was not one of the great print-makers of the 19th century, and we may not even think of Vauxhall Bridge as one of the landmark bridges of London. This print is not very big, at 54 x 107mm (just over 2 x 4 inches), so does not make a great impression on the viewer, and it was not even the first print of Vauxhall Bridge to be published. But it is less for the quality of the print than for what it represents that it is included here – its subject is two of the most revolutionary new buildings in London in the early 19th century. (fig.1) One, a bridge, is light-weight and elegant, representing movement and freedom; the other, a prison, is all too solid and menacing, speaking of nothing but captivity and oppression. |

| So this is more than just a standard view of two large buildings. Varrall's image is beautifully composed; the contrasting buildings themselves are in the middle ground, balancing each other, the one as important as the other. Beyond them is a background including a windmill and a paddle-steamer belching smoke, and in the foreground we see several sailing and rowing boats working and at rest. Much of the print is devoted to telling us, its audience, that it is a windy day - the ripples on the water, the steep attitude of the little sailing boat in the centre, the windmill, and the column of smoke all speak clearly of wind, probably a brisk south-westerly. |

| Varrall is also pointing out that the Thames is still very much a working river, with transport, industry, and just everyday life depending upon it. The new bridge makes a strong visual link between the two sides of the composition, but it is also a solid link between the two banks of the river, allowing vehicles, animals, and pedestrians to pass easily over it at any time of day. Finally, like Turner in his Fighting Temeraire of twenty years later, Varrall (who worked with Turner in the 1820s) is foretelling the coming supremacy of new technology over old, with both artists choosing the paddle-steamer as the harbinger of modernity. The Thames, once a bustling highway for boats of all sorts, is fast becoming merely a barrier to be crossed, and, although the flotilla of wherries off Vauxhall Stairs (between the sailing boats and the bridge on the left-hand side) still represents the old and much favoured way of reaching Vauxhall Gardens by water, it is now overshadowed by the bridge and by the distant steam-boat, which have become the new, more convenient, and cheaper, if less romantic, methods. |

| The artist is even showing us that his drawings for this print were executed in the Summer (the trees are in leaf), at midday (sunlight on the south walls of the Penitentiary), and just as a storm was passing (the stratocumulus clouds travelling north-eastwards). As this print was first published as an illustration in a London guide book on 1 April 1817, it is likely that the summer in which Varrall was working on it was in fact the 'summer' of 1816. |

| As everybody now knows in this bicentenary year, 1816 became known internationally as 'the Year without a Summer' because of the appalling weather aggravated by the massive eruption of the volcano Mount Tambora in Indonesia. Before their 1816 season opened on Monday 3 June, the proprietors of Vauxhall Gardens must have been looking forward to a record-breaking season – not only was access just about to be made very much easier by the new bridge, but it was also true that the whole country was still in a celebratory mood, following Wellington's final victory over Napoleon at Waterloo the previous June; in addition to this, Vauxhall was about to unveil its new secret weapon amongst its entertainments - the sensational Parisian tight-rope dancer Madame Saqui. |

| The fine and sunny opening evening at Vauxhall gave false hope; the 1816 season as a whole, dogged by wet, stormy and cool weather, produced an unprecedented £3,000 loss for the proprietors; it reached a low-point on the evening of 27 June 1816, the only evening during the entire two hundred year history of Vauxhall Gardens in which not one single paying customer arrived. So as to fulfil their contracts, the musicians played, and the singers sang, but only for the benefit of the rest of the staff and of each other. |

| This summer (2016), it is exactly two centuries since the first Vauxhall Bridge was opened, and since Varrall first drew it. This bridge spanned the River Thames from Vauxhall Cross on the east (or Surrey) bank to Mill Bank, near the Roebuck Inn on the west (or Middlesex) bank. Vauxhall Bridge Road on the west bank was created at the same time, intended to kick off a building spree on what had been gardens and fields, later described by Charles Dickens as a marshy waste-land choked with weeds and sedge. House-building on both sides of the bridge was in fact rather slow to take off, and the Vauxhall Bridge Company's shareholders, who had paid for it to be built, had to wait two or three decades to see any significant return on their investments, generated by tolls on the users of the bridge; these users were mostly visitors to Vauxhall Gardens, and casual spectators of the spectacular and hugely popular Vauxhall balloon flights, firework displays, and rowing and sailing regattas for all of which the bridge was an excellent grandstand, costing only a penny for pedestrians, instead of the normal four shilling admission charge to Vauxhall Gardens itself. |

| Both the bridge and the later railway station were constructed at Vauxhall Cross partly because of its proximity to Vauxhall Gardens, which, it was rightly believed, would generate both passengers and income. As it happened, it would also generate a new name for the bridge, which was originally christened Regent's Bridge, but which, by popular usage, soon became Vauxhall Bridge, after its most important destination. |

| Even though it has never really caught the public imagination, the first Vauxhall Bridge (replaced by the present one in 1906) was in fact remarkable for two main reasons; the first is that its building was funded entirely by private investment, at £100 per share; the second is that it was the first iron bridge over the Thames. It was over 240 metres long, its nine cast-iron arches supported on eight stone piers and two abutments. It was opened to horses and carriages on 24 July 1816, having already been opened to foot passengers seven weeks earlier, on 4 June. For a fuller history of the bridge, see http://vauxhallhistory.org/vauxhall-bridge/ |

|

|

fig

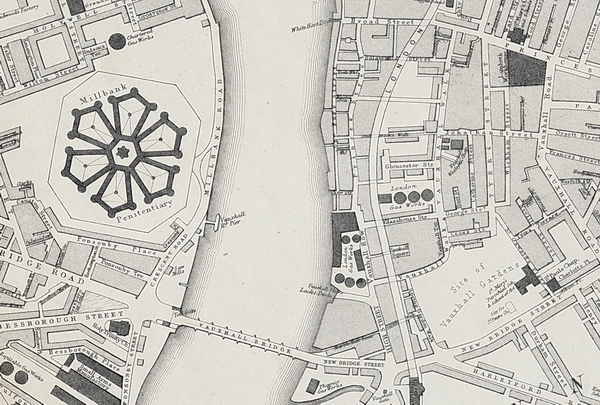

2. Cassell's 1863 Weekly Dispatch map of London

|

| The other main subject of the Varrall print, the General Penitentiary for Convicts on Millbank, was, like Vauxhall Bridge, opened in 1816, so when the print was made by Varrall, and published in David Hughson's 1817 Walks through London, these were the two most remarkable modern buildings in London, adjacent to each other. They both appear on Cassell's 1863 Weekly Dispatch map of London (fig.2), in which the Penitentiary and the site of Vauxhall Gardens (closed just four years earlier) balance each other on either side of the bridge; the Penitentiary within its octagonal wall, at sixteen acres, is larger than Vauxhall's twelve, but the high contrast of the two sites' purposes cannot help but give us pause for thought. |

| The very top right-centre of this illustration, on the east bank of the river Thames must represent the point where Varrall sat to create his drawing – could the sailing barges in his left foreground be in White Hart Dock? Today, this is one of the very few surviving parish docks on the Thames; first created in the 14th or 15th century, it was re-built c.1868 as part of the Albert Embankment works, and used as a commercial dock by the nearby Doulton pottery works until 1956; in 2009 it was cleaned and restored and became the focus for a group of site-specific boat-inspired sculptures. The map also shows the new railway line snaking in towards Waterloo, with Vauxhall Station just to the right of what the map calls 'Vauxhall Gate', but which is, in fact, Vauxhall Cross, at the very bottom of the image towards the right. |

|

|

fig

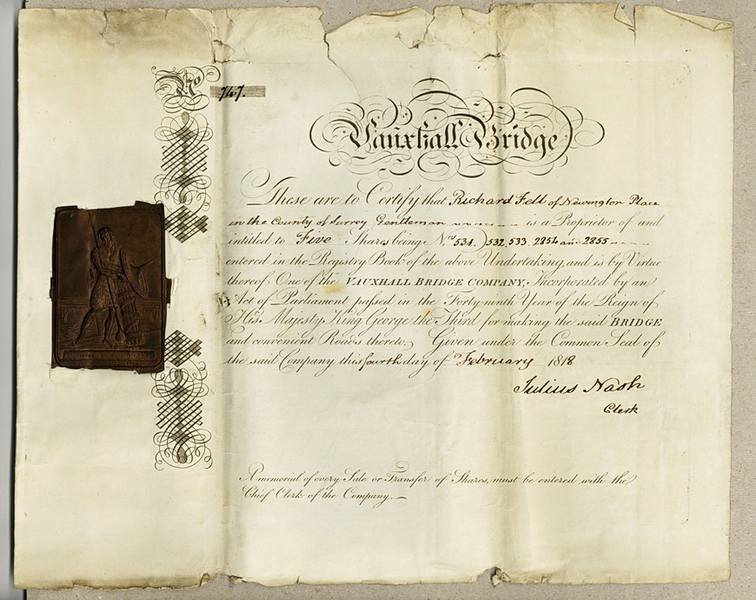

3. Vauxhall Bridge share certificate (image courtesy of vauxhallhistory.org).

|

| The Penitentiary, with 860 cells, was the first prison to have been originally designed on Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon principle (apparently inspired by the Ranelagh Rotunda), and the first purpose-built 'National Penitentiary'. Because of the boggy ground on which it was constructed, its builders were forced to develop a brand new type of foundation - the concrete raft – which has been widely used ever since. This necessity contributed to the huge cost of the prison, which eventually came to around £500,000, almost double the cost of its neighbour Vauxhall Bridge, which, even with the added costs of approach roads (share certificates clearly stated that the money was 'for making the said Bridge and convenient Roads thereto'), and of compensation to Battersea Bridge and to the Huntley Ferry, a Sunday ferry service to Vauxhall Gardens, cost just under £300,000. Fig. 3 illustrates one of a group of Vauxhall Bridge share certificates to have miraculously survived; this one, certificate number 747, complete with its copper seal, indicates that Mr. Richard Fell, Gent., of Newington Place, bought five shares in February 1818. |

| The Penitentiary was opened just three weeks after the bridge, when, on 26 June 1816, the first prisoners, all women, were admitted; the first occupants of male cells arrived seven months later. The boggy ground, which had incurred so much additional cost, also contributed to the Millbank Penitentiary's failure as a modern rational and reforming institution, due to the unhealthy setting; disease, especially cholera, was endemic, killing dozens of inmates. In 1842, Millbank was replaced as the 'National Penitentiary' by the more satisfactory 'Model Prison' built on higher ground at Pentonville. After this, Millbank became a temporary holding facility for convicts who had been sentenced to transportation to the Colonies, and who may have to wait up to six months for a suitable ship. It was this unpromising period which gives the Penitentiary its greatest claim to modern fame; prisoners being transferred to the ships for transportation, especially to Australia, were taken down to the lower levels of the building for secure boarding into the small boats that would ferry them to the London docks; these prisoners were said by fellow inmates to be 'going down under', a phrase still in use today, but now for journeys all the way to Australia, rather than just downstairs. There is another theory that the word 'Pom', Australian for an Englishman, derives from the initials 'P.o.M.' for 'Prisoner (or Penitentiary) of Millbank'. |

| After the early 1850s, when transportation as a punishment was being phased out, Millbank was used as a local jail, and later as a military prison, before its short life came to an ignominious end with its demolition in the 1890s. The sixteen acre site was later partly occupied by the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain, originally opened as the National Gallery of British Art in 1897. Francis Hayman's painting The Play of See-Saw, painted for one of the supper boxes at Vauxhall Gardens, is now owned by Tate Britain (T00524, presented by the Friends in 1962), although it is rarely on display there. It was last shown at the exhibition The Triumph of Pleasure at the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury in 2012. |

|

|

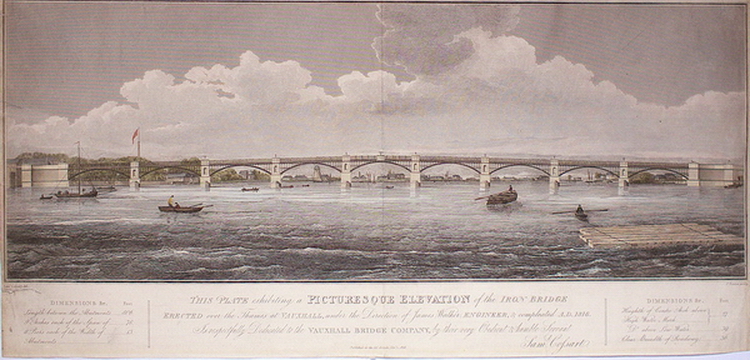

fig.4.

Picturesque Elevation of the Iron Bridge Erected over the Thames at

Vauxhall, engraved by James Basire after a design by Samuel Cossart,

dated 1 November 1816.

|

| There are many 19th-century prints of Vauxhall Bridge, mostly showing only the bridge itself, without the Penitentiary next to it. Varrall's may not be the first, the biggest, or the most decorative, but it does have claims to be the most remarkable and the most perceptive of all of them. For the earliest, and possibly also the largest, print of the bridge, we should probably go to the Picturesque Elevation of the Iron Bridge Erected over the Thames at Vauxhall, engraved by James Basire after a design by Samuel Cossart, dated 1 November 1816 (fig.4). This print, 61cms / 24" wide, showing a frontal view of the whole structure from the downstream side, was dedicated by the artist to the Vauxhall Bridge Company, who may have commissioned it; it includes a series of dimensions of different parts of the bridge within the inscription. Although it does show details of small boats on the river, and structures on the banks, it is nevertheless little more than an accurate architectural elevation of the bridge, as its title suggests. A tiny anonymous version of this print, only 105 x 18mm, from Samuel Leigh's 1827 New Picture of London, possibly the smallest print of the bridge, is reproduced at the foot of this article (fig.6). |

|

|

fig.

5. Vauxhall Bridge engraved by Henry Winkles in Tombleson's

Views of the Thames and Medway of 1833/4

|

|

For

the more romantic or picturesque approach, William Tombleson is our

man (fig.5); his hugely popular book, Tombleson's Views of the Thames

and Medway of 1833/4 includes amongst the eighty plates an oblique

view of Vauxhall Bridge seen from the upstream Millbank side, engraved

by Henry Winkles; several people and a dog populate the riverbank, where

a boat is upturned for repair, and a fisherman mends his net under one

of the pollard willow-trees. The white sail of a small boat points away

from the bridge in the distance. The whole imaginative composition is

enclosed in a decorative border of roses on trellis, blocking from our

minds the unromantic industries and slums on the opposite bank, and

the new gasworks at Vauxhall Gardens, let alone the menacing presence

of the Millbank Penitentiary just off to the left.

|

| It can often be well worth taking a closer look even at prints that may at first appear uninteresting. Unlike Tombleson, Varrall has not shied away from including the less picturesque aspects of this western end of riverside London, and yet he has produced a remarkably attractive, interesting and informative engraving. His composition, with its optimistic blowing away of the storm, looks to the past of sail and horse with fondness and to the more technological future with hope. |

|

|

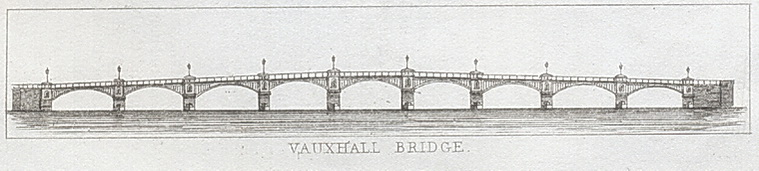

fig.

6. Vauxhall Bridge from Samuel Leigh's New Picture of London

1827

|

| Back |

| [If you would like to comment on this article, please contact me] |