|

'THE

DELIGHT OF ALL PERSONS OF REPUTATION AND TASTE'

|

|

Vauxhall

Gardens 1661-1859

|

|

fig.1 C. H. Simpson Esq., Master of Ceremonies at Vauxhall from 1797 until his death aged 65 in 1835 CONTENTS 1. Introduction

|

|

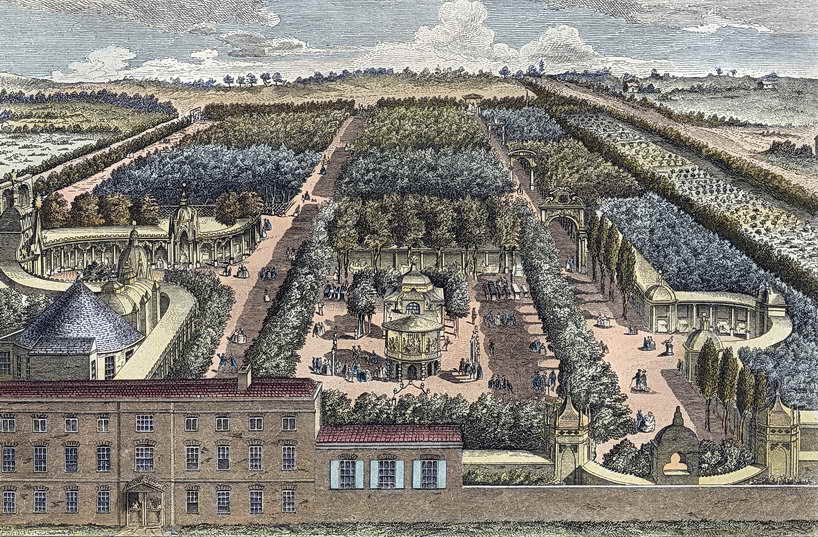

fig. 2 The Temple of Comus Piazza with visiting families Vauxhall Gardens was re-launched in 1732 as the first and most significant of the true Pleasure Gardens of Georgian London.[1] Commercial pleasure gardens, an English invention, were privately-run sites of entertainment; they were often situated on the outskirts of large towns or cities, and paying visitors were entertained in the summer months with music and company; refreshments were available at a price. Pleasure gardens, as their name implies, were mainly outdoor spaces, though sometimes with an assembly room or concert hall, and they were normally open in the evening, after the working day; anybody who could afford the admission price and who was at least respectably dressed would be admitted (figs. 2 & 3).

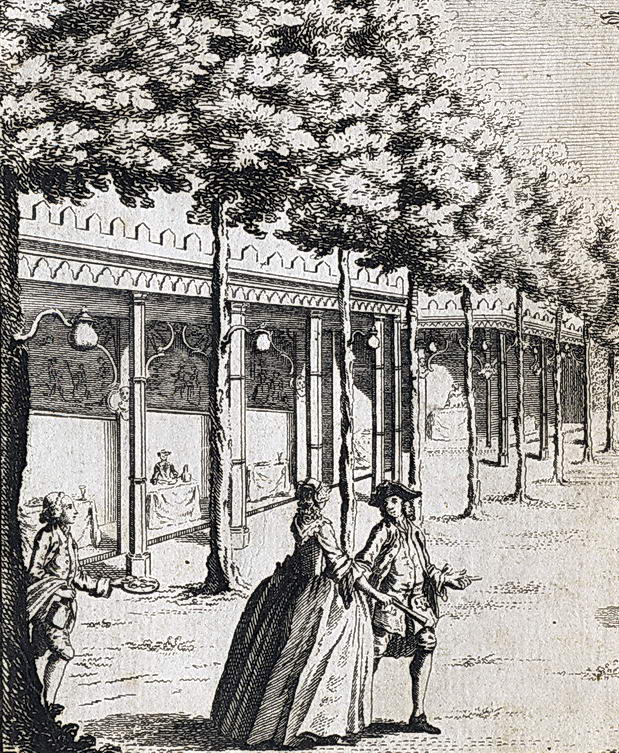

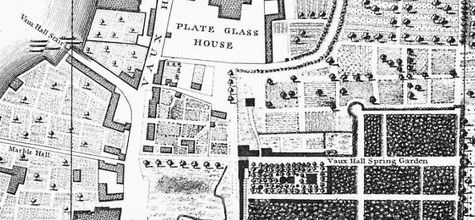

fig.3 The Grand South Walk, with visitors promenading and having supper By the end of the 18th century, there were at least five dozen pleasure gardens of all types and sizes in and around London, but Vauxhall's chief competitors were Marylebone Gardens near what is now Harley Street,[2] and Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea,[3] opened in 1737 and 1742 respectively. At Vauxhall the gardens were normally open from 5 or 6 p.m., closing when the last visitors left, which could be well into the following morning. The season lasted from early May until late August, depending on the weather – the earliest opening date on record is 28 April (in 1740), and the latest closing date is 29 September (in 1851). Opening days were notified in the press. One of the great enduring attractions of Vauxhall was the artificial illumination, activated after sunset. Before the lights were lit, Vauxhall was a respectable wooded park where families with children could safely enjoy a rural promenade; after dark, the walks, now inhabited by courting couples, sexual predators and pickpockets, became more threatening, despite the presence of London's first professional police force.[4] There is no modern equivalent of Vauxhall Gardens, and public attitudes and appetites have altered so fundamentally since the 18th century that it would be impossible to recreate it as anything except a historical curiosity today. Aspects of Vauxhall reappear in arts festivals, musical events and holiday resorts today, but these are isolated features, which can convey nothing of the magic of an evening's outing there in the 1750s. The closest equivalent in modern times is the partnership of Architect Mark Fisher and engineer Jonathan Park, in their extraordinary collaborations with Roger Waters and Gerald Scarfe for the astonishing rock concerts of the Pink Floyd's The Wall tours (World Tour 1980-81, and its revival in Berlin, 1990).[5] In their combination of avant-garde design, first-rate contemporary music, dramatic atmosphere and illuminations, and pure escapism, they replicate something of the thrill of the Vauxhall evening, and of the sensory dream-world apart that Vauxhall represented. The site of Vauxhall Gardens, adjacent to Vauxhall Railway Station (which was situated there for the convenience of Vauxhall's visitors), is marked today by a small park, owned by the London Borough of Lambeth, with a city farm at one end; its boundaries are Kennington Lane, Goding Street, St Oswald's Place, and Vauxhall Walk. It was first opened for public use soon after 1660, as a rural tavern and place of assignation called the New Spring Garden; it was laid out on a piece of ground then owned by the Prince of Wales as part of his Duchy of Cornwall estates. The Duchy leased it to tenants, and in the 17th century the land was planted with commercial hardwood trees, such as sycamore, lime and elm;[6] the trees were grouped within several rectangular 'wildernesses', separated by straight avenues in a grid pattern, a layout which was never significantly altered until the gardens were demolished in 1859. Among the trees were fruit bushes and perfumed flowers. The tavern stood on its own at the western boundary of the plantation, nearest the river, where Goding Street is today. The gardens did not finally close until July 1859, after almost two centuries as a hugely successful business. During that time, it underwent many changes in its architecture, its attractions and its audience, but its life can meaningfully be broken down into just three main periods of about seventy years each – the first (or 'New Spring Garden' period) from 1661 until 1728, the second ('Tyers Years'), from 1729 until 1792 when it was owned and managed by two generations of one family, and the third from 1793 until 1859 (the 'Capitalistic Mass Entertainment'), when it was transformed from the elegant and fashionable rendezvous it had become into a more populist commercial venue for balloon flights, fireworks, circus performers, massed bands and other spectacular entertainments.

'Vauxhall pleasure gardens, on the south bank of the Thames, entertained Londoners and visitors to London for 200 years. From 1729, under the management of Jonathan Tyers, property developer, impresario, patron of the arts, the gardens grew into an extraordinary business, a cradle of modern painting and architecture, and a music venue vital to the careers of Thomas Arne and George Frideric Handel: the Music for the Royal Fireworks was first played here, in a rehearsal attended by up to 12,000 paying customers. A pioneer of mass entertainment, Tyers had to become also a pioneer of mass catering, of outdoor lighting, of advertising, and of all the logistics involved in running one of the most complex and profitable business ventures of the eighteenth century in Britain.' Prof. John Barrell, distinguished scholar of eighteenth-century England, in the Times Literary Supplement, 27 Jan, 2012, no. 5678, p. 3 'This was always a raucous place, but a temple of the muses too. Under the management of its gifted, quixotic master of ceremonies, Jonathan Tyers, it was perhaps the first public art gallery, hung with paintings by Hogarth and Hayman. The buildings – first Palladian then Gothic and exotic – were splendid and the music inspired. The Vauxhall season was unmissable. Royalty came regularly. Canaletto painted it, Casanova loitered under the trees, Leopold Mozart was astonished by the dazzling lights. The poor could manage an occasional treat. For everyone it was a fantasyland of wonder and pride.' David Blayney Brown of the Tate Gallery, in The World of Interiors, October 2011 '[Vauxhall Gardens was] an exotic outdoor pleasure ground and a new type of public resort that had never been seen before. There, for around a shilling, the gardens' diverse entertainments provided amusement for all – be they male or female, old or young, rich or poor. Such was its success that copycat creations soon followed. From Bath to Nashville, Tennessee, Vauxhall-inspired gardens were founded in the hope of recreating its profitable magic.' Hannah Greig of York University, in History Today, October 2011

3. History 3.1 The 'New Spring Garden' 1661-1728 The first published mention of Vauxhall Gardens as a resort of pleasure appears under its original name in the diary of John Evelyn, who recorded on 2 July 1661[7] that 'I went to see the new Spring-Garden at Lambeth a pretty contriv'd [meaning well designed] plantation.' His fellow diarist Samuel Pepys was to become a regular visitor; Pepys was the first to enumerate some of the perennial delights of a visit, in particular the boat-trip across the Thames, the song of the resident nightingales, and the seductive women who made Vauxhall one of their favoured places of work.[8] These three subjects were all repeated over forty years later at the beginning of the 18th century by Joseph Addison in his Spectator magazine, when he has Mr. Spectator visit the New Spring Garden with his friend Sir Roger de Coverley;[9] the two are rowed across the Thames by a wooden-legged war veteran, and wander in the gardens listening to the nightingales; much to their horror, their pleasurable musings are interrupted by a 'wanton Baggage' who invites them to share a bottle of mead with her. On leaving the gardens, Sir Roger complains to the landlady (probably Hannah Hill)[10] that he would be a more regular visitor 'if there were more nightingales and fewer strumpets.' Because of this dubious reputation, the New Spring Garden entered the literature and drama of the period as an archetypal setting for romance, intrigue and adventure.[11] At this time, the Vauxhall area of south Lambeth was largely made up of pastureland, market gardens and orchards, with some industrial activity, notably glass and ceramic production, and a few houses.[12]The New Spring Garden, with its eight acres or so of wooded rectangles and avenues, took advantage of this rural environment, becoming known as a pleasant place to escape the noise, smells and dangers of the city. It was also known for its relaxed attitude towards amorous encounters of all sorts. Scattered among the trees were numerous roofed wooden arbours with pub-like names ('The King's Head', 'The Dragon', 'The Royal George' etc.,[13] as well as old coach bodies adapted as makeshift arbours for visitors who wanted to be private; disused boats were hung from the branches as a retreat for men who wished to smoke.[14] Smoking was later banned as antisocial, and pet dogs were excluded for a similar reason.[15] The opening hours and admission charges of the gardens at this period are not known. Samuel Pepys, who used it as an evening resort after work, records that occasional informal entertainments were available in the form of strolling musicians, buskers, and acrobats.[16] Some of the visitors, including Pepys himself, provided impromptu entertainments of amateur music and song. Alcoholic beverages, cold meats, and tobacco or snuff were all available to buy at exorbitant cost and questionable quality in the tavern. Pepys wrote, on 28 May 1667, that visitors could spend as much as they liked 'or nothing', implying that admission was free at that time. According to an article in The Times newspaper of 20 May 1789, a sixpenny charge was later imposed.

3.2 The Tyers Years, 1729-1792 In March 1729, 'Vauxhall Spring-Gardens', as it was known, was sub-let to a new tenant. A young tradesman from Bermondsey, whose family had worked profitably in fellmongering, the nastier end of the leather industry, for several generations; he believed he could see a gap in London's entertainment industry. Jonathan Tyers (1702-1767) saw in the slightly disreputable old garden an opportunity to provide for London a new type of entertainment; he was also keen that his pleasure garden should be capable of imparting a moral message to his visitors. In taking on the ownership and management of the Spring Gardens, he determined to clear out the prostitutes and the immoral behaviour, and to replace them with an 'innocent and elegant' entertainment where respectable Londoners of all classes, with their families, could enjoy a civilised, enjoyable and even educational evening out; this was something that was not otherwise available to ordinary Londoners. Early eighteenth-century London was a noisy, dangerous, smelly and violent place;[17] it was also riven with hypocrisy, corruption and wickedness of all sorts. In taking on and sanitising the New Spring Gardens, Tyers intended to provide an escape from this, but also an example that the rest of London could follow. His pleasure garden would kick-start the civilisation of Georgian London, turning it into a worthy capital city for the newly-united Great Britain. He would exclude nobody from his gardens simply because of their class or status, but anybody who did choose to visit would gain, while there, a subliminal polite education, and would leave a better person. Jonathan Tyers would have agreed wholeheartedly with Thomas Jefferson that 'all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.'[18] The egalitarian and 'polite' nature of Tyers's vision, both entirely novel concepts to London, would be the cornerstones of his new pleasure garden for the rest of the century, and an underlying key to their longevity. To start with, however, they almost derailed the project in its first year. For the 1732 re-launch party, which he called a Ridotto al Fresco, Tyers created a centrepiece display of five tableaux showing the evil consequences of self-indulgence and intemperance.[19] Unsurprisingly his self-indulgent and pleasure-seeking audience were not best pleased. Had Tyers not subsequently sought the advice of his friend the artist William Hogarth, his new venture could have sunk without trace. Hogarth was himself about to launch his series of 'modern moral' paintings and engravings, having realised that a moral message is best received when it is disguised with humour and enjoyment. Following his meeting with Hogarth, Tyers created at Vauxhall the 'Grove', a large open area inside the entrance to the gardens, where the three main tree-lined avenues met. He surrounded the rectangular Grove with buildings; on the west was already Spring Gardens House (1717), where the proprietor lived, with its ball-room to its south, and around the remaining three sides Tyers had straight neo-classical roofed colonnades in the plainest Tuscan order erected. This orderly Roman-style piazza was intended as the dignified setting for the main entertainments of Tyers's visitors, who would watch each other promenading, indulging in polite conversation, listening to good music, and partaking of refreshments. Beyond the Grove, the old wooded wildernesses remained, and the veneer of civilisation gave way to a less orderly and darker experience (fig. 4).

fig.4 A General Prospect of Vauxhall Gardens from the west, with the proprietor's house and the Prince's Pavilion (with three shuttered windows) in the foreground Tyers's master-stroke was to convert his house's ball-room into a raised pavilion with a private dining room and an open loggia for the use of Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, Vauxhall's ground-landlord. Prince Frederick was the most popular member of the royal family, and his youthful energy gave him broad appeal. Wherever Frederick went, fashionable society was sure to follow. Rejected and loathed by his parents, Frederick needed a new public stage from which to show himself to his future subjects. As an attractive and already public part of his own estate, populated by fashionable people out to enjoy themselves, and policed by Tyers's force of constables, Vauxhall was the ideal platform for Frederick; and Frederick was the ideal patron for Tyers, who could then use the young royal visitor as the cornerstone of his publicity, and the inspiration for much of his decoration.[20] In identifying Vauxhall so closely with the prince, it might be assumed that Tyers was giving his gardens a political leaning towards the opposition Tory party; however, he was astute enough to realise that this would have alienated half his potential audience at a stroke, so no such political alliance was ever explicit in Vauxhall's message, and Tyers's audience continued to be a rich mix of the widest possible public. The Vauxhall visitor and the London theatre-goer would have had a great deal in common, and, in many cases, would have been the same people at different seasons. To many foreigners the London theatres and its pleasure gardens were the greatest attractions that the city had to offer. For those who were more easily pleased, there were also cabinets of curiosity, fairs, puppets, freak shows, taverns, ballad-singers, menageries, and an almost infinite number of similar shows and amusements. To the dismay of many visitors, Londoners had a strong predilection for the cruel sports, involving violence between men and between and towards animals. The pleasure gardens offered a real alternative, and a place where families with children could relax. Jonathan Tyers made a point of tacitly appealing to a female audience through his publicity and through the attractions and artworks of Vauxhall, partly because he was aware that it was frequently women, rather than their husbands, who made the decisions as to a family's social amusements. One of the 400 visitors to Tyers's Ridotto al Fresco in 1732 was the composer George Frideric Handel. Like Hogarth, Handel was always ready to seize any opportunity for a new outlet or a new audience. Vauxhall promised enormous potential for an enterprising musician, but only if the old informal and populist approach to performance at Vauxhall could be replaced with a more considered and meaningful programme. One of Handel's colleagues, the impresario John James Heidegger had been employed by Tyers to organise his Ridotto, and it was probably Heidegger who not only introduced the composer to the entrepreneur, but who also persuaded Tyers to place high-quality music at the physical and notional centre of his project, making it his chief entertainment.

fig.5 The Orchestra and Organ buildings in 1751, with fashionable visitors listening to the music The new octagonal bandstand or 'Orchestra' at Vauxhall, built in the middle of the Grove (fig. 5), was one of Tyers's most revolutionary buildings and possibly the first building in London designed specifically and solely for the performance of music.[21] Unveiled in 1735, it not only provided a raised stage for the musicians, or 'Band', so they could be seen and heard by everybody in the Grove, but it also effectively separated the Band from easy contact with their audience so that requests for popular pieces of music, which had been the previous method of programming, became a thing of the past. This allowed for the introduction of newly-written works by contemporary composers, within a complementary pre-organised programme. Handel and his peers took full advantage of this, but Tyers, always the first to put his own stamp on the public face of Vauxhall, stipulated that his music should be specifically English music, composed and performed by English (or at least English-based) musicians; Handel, of course, was German-born, but his music was generally accepted as English music, written in England for an English audience. In promoting English music, Tyers differentiated Vauxhall from the London theatres and concert rooms, where European, especially Italian, music and performers held sway. Vauxhall was one of the few places where good contemporary English music could be heard on a regular basis. After the construction of the Orchestra, and the appointment of a permanent band, Tyers instituted an admission charge of one shilling, the equivalent of about £12 to £15 today. This charge remained unchanged for almost sixty years. The composer Thomas Augustine Arne was taken on by Tyers as his in-house composer, and effectively his director of music, in 1745. It was Dr Arne who persuaded Tyers to introduce song into his evening programmes, alongside the instrumental music and organ concertos.[22] From that time, the Vauxhall song, usually pastoral ballads, songs of love or patriotic airs, became the most popular element of the entertainment there. The songs were not only written by English composers and lyricists, but they were also sung in English by British singers, so were much easier to understand than the Italian opera which was then so fashionable among the gentry. Published song-sheets were marketed to spread the fame of Vauxhall to drawing-rooms all over the British Isles, as well as overseas. Many of the songs written specially for Vauxhall became hugely popular and are still familiar today – Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill, by James Hook, and Henry Carey's Sally in our Alley are just two examples of many. Boasting an average of 1,000 visitors every evening during the hundred or so days of summer, Vauxhall, by continuous repetition of its evening programme, created the first true mass audience for high-quality music and popular songs. Vauxhall was also the venue for important musical occasions, and the first performances of major works. The most talked-about musical composition of the 1740s was Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks, and Jonathan Tyers was determined, even in the face of opposition from the composer himself, to host the rehearsal at Vauxhall.[23] He secured this by offering to provide the oil-lamps for the main performance in Green Park, and thirty of his employees to help run the event. On the morning of 21st April 1749, several thousand people made their way to Vauxhall to witness the great rehearsal, the largest crowd the gardens had ever seen. Even if the attendance figures were only half the twelve thousand excitedly reported in the press, the event produced not only some very useful income for Tyers before his season had started, but also some wonderful word-of-mouth publicity, just as he knew it would. The success of this event led to Vauxhall becoming the focus and the regular venue for national and patriotic celebrations; coronations, royal birthdays, and military victories were all celebrated here with special 'gala' evenings, and with temporary and permanent additions to the music, songs, buildings, and works of art. As for the Fireworks Music rehearsal, the admission charge was always raised for special events, sometimes to double or triple the normal rate. Although it is often asserted that 'Vauxhall Gardens' as a name did not appear until the 1780s, it was, in fact, current much earlier. In 1738, the poet and translator John Lockman, who Tyers employed as his publicity manager, provided the words for one of the songs published in George Bickham's lavish song-book The Musical Entertainer, called The Invitation to Mira, requesting her Company to Vaux Hall Garden. It may well have been Lockman who re-branded the Gardens through his popular song-lyrics as 'Vauxhall (or Vaux Hall) Gardens'. Seven years later, the new name appears to be more generally accepted; Thomas Arne's first volume of Vauxhall songs, Lyric Harmony', published in 1745, proudly advertises on the title page that all the songs are 'As perform'd at Vaux Hall Gardens'.[24]

fig.6 A portrait of the painter Francis Hayman While lending their ears to the music and songs, visitors were encouraged to use their eyes as well. It would have been impossible for Hogarth not to suggest to Tyers at that first meeting that he include contemporary visual art in his decorations. Hogarth had established the St Martin's Lane school of art in 1735, and he was training painters, sculptors, architects and designers. Tyers's Vauxhall would provide the ideal vehicle for the work of his colleagues and students. He introduced Tyers to his close associate, the theatrical scene painter and illustrator Francis Hayman (1708-1776) (fig. 6). Hayman became Tyers's artistic director for more than two decades, designing painted decorations for each of the fifty or more 'supper-boxes' created within the colonnades that bordered the Grove (fig.7), and producing at least eight large oil paintings to decorate two of Tyers's main buildings – four Shakespearean scenes in the Prince's Pavilion, and four huge canvases of British victories in the Seven Years' War in the Pillared Saloon. All of these paintings were intended to show positive and amiable aspects of the British way of life – its rural games, its theatre and literature, its urban amusements, its traditions, and its military prowess. Many of the paintings, however, also carried a concealed moral message, demonstrating the input of both Tyers and of Hogarth.

fig.7 'The Milkmaids Garland', an engraving of one of Hayman's supper-box paintings, from a contemporary magazine. The original painting is now in the Victoria & Albert Museum. Moral messages also underlie the remarkable sculpture that was Tyers's most significant single fine art commission. The portrait statue of George Frideric Handel by the London-based French sculptor Louis François Roubiliac is a life-sized full-length sculpture in white Carrara marble showing the seated composer relaxed and informally dressed, at work.[25] As a portrait, its relaxed modernity was unusual enough (fig. 8), but for Tyers, it had to perform several jobs: first, it gave him an artistic credibility, both among visual artists and musicians, so that they would be happy to work for him at Vauxhall; second, it identified his garden closely with the most popular composer; and, third, it promoted the moral virtues of hard work and of humility. As far as Handel himself was concerned, the sculpture contributed to his celebrity, and it kept his image constantly in front of a fashionable public at a time when his music and his bank balance were suffering something of a crisis.[26] The sculpture was unveiled on the first night of the 1738 season, strategically placed in a break in the southern row of supper-boxes, facing the Orchestra. Here, it could be seen from the entrance, and it became the first sight that first-time visitors were supposed to admire. It provided a great deal of useful publicity for Tyers's gardens, both in the press and word-of-mouth, and it became one of the standard iconic portraits of Handel, used on several modern editions of his works.

fig.8 Roubiliac's statue of Handel, as shown in the Illustrated London News in 1859 Roubiliac's statue of Handel epitomised modern art in the 1730s. It set the tone for the rest of the arts to be seen and heard at Vauxhall during the remainder of Tyers's proprietorship. The paintings were all in the latest style, influenced by the European Rococo movement, and the music and song was all newly-written each season, sometimes specifically for performance at Vauxhall, by some of the best composers of the time. In fact Tyers himself became a significant patron of art during his time at Vauxhall, profoundly affecting the development of visual and musical arts in Britain, and filling his two homes with modern works of art. The architecture of Vauxhall was youthful and modern, and very much on a human scale; it was intended not to impress but to provide a flattering background for elegant and fashionable people, and a fitting environment for visitors and performers alike. The setting was constantly updated to keep it looking fresh and new. Regular visitors to Vauxhall were thus made fully aware of all the latest fashions, in art, music, design and costume, and these were then quickly transmitted to the rest of London and Great Britain, and even overseas to Europe and America. The supper-boxes, created within the colonnade around three sides of the Grove, were like theatre boxes, open at the front, and large enough to seat six or eight people on fixed benches around a table. A party of visitors to Vauxhall would order their supper immediately on entering, and they could choose either to dine at one of the tables scattered around the Grove or else to be allocated a supper-box, identifiable not only by a number, but by the painting hung in the back of each one, to which they could return after promenading in the gardens or listening to the music (fig. 9). Suppers were served from about 9 p.m., and consisted of light refreshments – thinly-carved cold meats and salads, pastries and cakes, as well as wines, beers, ciders and punch, all served by well-trained and speedy waiters.[27] As suppers were being served, the great special effect of Vauxhall was enacted; a whistle was blown, the signal for lamp-lighters to hurry to their allotted stations around the Grove; at a second whistle, they would light cotton-wool fuses which had been set up during the day to guide the flame from one oil-lamp to another; in this way, it was said, thousands of lamps could be lit 'in an instant'– an effect which, before the days of electricity, must have been staggering.[28]

fig.9 A small detail from a 1752 engraving showing a row of supper-boxes with paintings at the back. A fashionable couple in the foreground and a waiter to the left. Typical 'bucket' lamps hang on the trees Whether by accident or by design, Tyers's Vauxhall became a feast for all the senses. The sweet country air, the excellent music, and the smartly-dressed visitors made a refreshing contrast to London's noisome streets, and daily problems and worries could be easily forgotten. The delicious sensory experience of being enveloped in a dream-world of perfumed flowers, charming music, fine design and beautiful works of art, especially at night, as well as eating and drinking good fare, and literally rubbing shoulders with elegant society, was a vivid, unforgettable and addictive experience which encouraged visitors to return again and again.[29] This and the royal patronage of the Prince of Wales contributed two significant ingredients to Vauxhall's undoubted success.

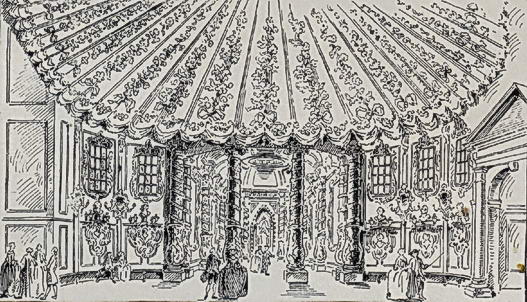

fig.10 The interior of the Rotunda, from a 19th century periodical The healthy profits that Tyers made, especially from the sales of his expensive refreshments, were always ploughed back into the business, or into acquisition of property outside the gardens to provide secure income for slack periods. Every year saw some new building, work of art, or attraction, or even additions to the physical extent of the gardens, which eventually covered about twelve acres. The 1748 season saw the new Rotunda building, intended as a concert room during wet weather (fig. 10); the first visitors in 1751 would have been amazed by the new semi-circular 'piazzas' opened up in the two main ranges of supper-boxes (fig. 11), and by the spectacular 'tin Cascade' in the following year.

fig.11 The 'Temple of Comus' Piazza of 1751, from a 19th century periodical In order to stay in touch with the latest developments, fashionable society would have to re-visit the gardens at least once every season. Because it was such an essential rendezvous, Vauxhall became an important focus for the exchange of gossip among the Beau Monde,[30] and, in a symbiotic relationship with the press, one of the chief platforms for the creation of celebrity in Georgian England. For well over a century, Vauxhall was the single biggest commercial visitor attraction in the country. Against all the odds, and despite the English weather, Jonathan Tyers, a tradesman from Bermondsey, had succeeded in making his invention into the vital meeting-place and habitual drawing-room for fashionable and aristocratic Londoners. An excellent scale model of Vauxhall Gardens c. 1750, with illuminations, which was made by Lucy Askew for the 1984 'Rococo' exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, is still in the museum's collection, and is still a useful tool for visualising the gardens as they looked in Jonathan Tyers's time.

3.3 'Capitalistic Mass Entertainment' fig.12a Thomas Rowlandson's famous print of 'Vaux Hall' of 1785

fig.12b Detail of the Rowlandson to show the right foreground group After his death in 1767, Jonathan Tyers's pleasure garden was passed to his second son, also called Jonathan (1728/9-1792). Despite the apparently seamless continuity, the 25 years of the younger Jonathan's management are marked by a singular lack of innovation or entrepreneurship, and only a handful of noteworthy events. Although he maintained what his father had created, he added very little to it, and was consequently responsible for a drop in the quality both of the entertainments and of the 'company' themselves. Thomas Rowlandson's famous watercolour Vaux Hall of 1784 (fig. 12a) represents the end of an era. The artist shows us a microcosm of the previous two decades, with some typical visitors (including Dr Johnson (probably), the Prince of Wales with the actress Mary 'Perdita' Robinson, and a clutch of journalists), typical refreshments being enjoyed by Johnson's party, typical music and song represented by the band and the soprano Frederica Weichsel, and typical socialising amongst all the visitors we can see, including the more sexually explicit encounters in the right foreground (fig. 12b). This hyperlink to an image of Rowlandson's Vaux Hall gives my version of the identifications of the people included by him, as well as a possible reason why it was painted, and for whom.

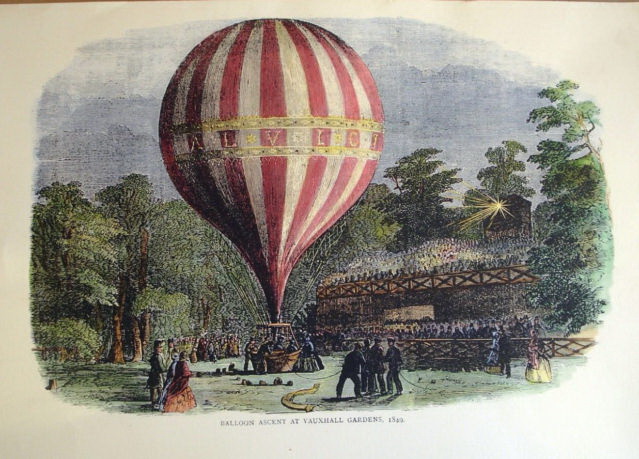

fig.13 Country-dancing in front of the Orchestra in 1822 When Bryant Barrett (1743-1809) took over the management following the death of Jonathan Tyers the younger (his father-in-law) on 21 March 1792, he had to dream up new ways of attracting visitors. He realised that his client base was changing, and that their needs and requirements were changing too (fig. 13). This new crowd, no longer satisfied just with music and people-watching, craved excitement, novelty and thrills. Firework displays, mostly created by Michael Hengler and his wife Sarah (née Field), fulfilled this need for a while, especially when accompanied by the exotic and rousing music of the in-house military bands and the exotic and raucous foreign bands. These diversions, though, were too commonplace to maintain the continuous repeat visits that Vauxhall required for its economic survival. Income receipts would have continued to dwindle had it not been for the introduction of the one activity guaranteed to exert a powerful draw on even the most jaded Londoner – ballooning. Without the income generated by spectators and participants in balloon flights, it is likely that Vauxhall Gardens would have closed considerably earlier than it did. The first regular Vauxhall flights, with André Jacques Garnerin at the helm, took place in 1802, and were never then dropped from the attractions. Garnerin's several flights in that first year included manned flights in gas balloons, using hydrogen as a lifting agent, and one spectacular 'Fire Balloon' on 20 July. On that evening, an unmanned balloon was sent up with a suspended structure below it carrying a pre-arranged firework display; as the balloon left the ground, the fuse was lit, and then a hushed few minutes passed while the balloon gained height over the gardens preceding a massive and spectacular pyrotechnic display high up in the air which closed with the balloon itself exploding in a fireball, accompanied by gasps from the vast crowd of spectators both inside and outside the gardens. This spectacular display would have been visible to most of London, and would have given the gardens' publicity a welcome boost. Vauxhall's balloon ascents were later taken on by the expert aeronaut Charles Green and his family, with spectacular success, and several technological advances. Green was able, for huge prices, to take passengers on his flights, which generated substantial income both for him and for Vauxhall (fig. 14). One major drawback of balloons, however, is that they need dry, still weather to fly. For those days when that was not available, the managers badly needed other forms of entertainment. But the solution of this problem had to await new management.

fig.14 The ascent of Charles Green's Royal Victoria Balloon at Vauxhall in 1849 Bryant Barrett's two sons, Revd Jonathan Tyers Barrett (1784-1851) and George Rogers Barrett (1787-1860) (great-grandsons of Jonathan Tyers the elder), took on the ownership of the gardens on the death of their father in 1809; although G. R. Barrett was notionally in charge, it is unlikely that either brother was able or inclined to involve himself in the day-to-day management. This role was delegated to professional managers like James Perkins (from c. 1804), and G. B. Flowers (from 1816), with the quaint C. H. Simpson, who Thackeray called 'that kind, smiling idiot' acting as Master of Ceremonies from 1797 until his death in 1835 (figs. 1 & 15),becoming a popular attraction in his own right.[31]

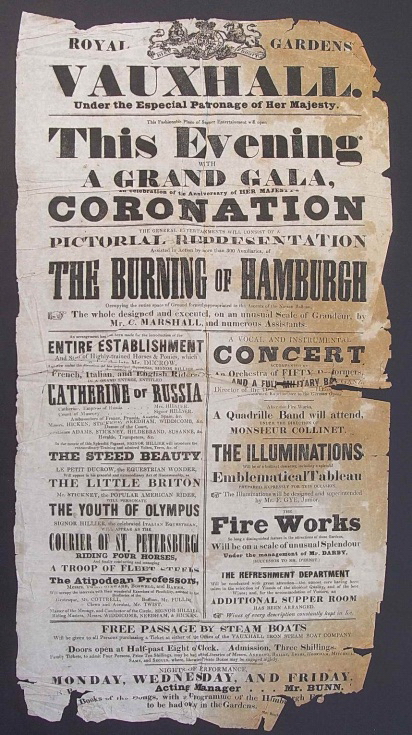

fig.15 Vauxhall in 1835 by George Cruikshank, with CH Simpson in the centre raising his hat It is not known who was responsible for Vauxhall's radical change of direction in 1816, but it was that year that saw the first appearance at the Gardens of the sensational Madame Saqui. Marguerite Antoinette Lalanne (1786-1866), known to the world as Madame Saqui, was the French tight-rope walker and rope-dancer[32] who had appeared to enormous acclaim at Covent Garden theatre. It was at Vauxhall, however, that her act truly blossomed in England – here she could set her rope as high and as long as she wanted, and here too she could combine her act with the music and fireworks already in place. Her finale in 1816 consisted of ascending to a considerable height up a mast set up at the eastern end of the gardens, and then running down the inclined tight-rope which had been extended from the mast half way down one of the main walks, surrounded as she ran by a storm of exploding fireworks. Unsurprisingly, this spectacular performance became a regular and hugely popular part of Vauxhall's entertainments for the next four years; after which other acrobats and tightrope walkers took over and developed Saqui's role. Madame Saqui's tight-rope act opened the doors to a plethora of circus acts, and Vauxhall's extraordinary advertising posters had to squash ever more information into the limited space available (fig. 16).

fig.16 A Vauxhall poster of 1842, for the anniversary of Queen Victoria's coronation, on 28th June In the 1820s, Jonathan Tyers's family finally gave up Vauxhall Gardens altogether. In 1821 they leased the Gardens to a business partnership made up of Thomas Bish, the celebrated lottery contractor,[33] Frederick Gye, his printer, and the theatre manager Richard Hughes, brother-in-law of Joseph Grimaldi; the lease was turned into an outright sale four years later. Together, Bish and Gye had formed the successful London Wine Company in 1817, and Gye formed the London Genuine Tea Company with Richard Hughes a year later, so Vauxhall looked like a logical extension of their twin businesses. Their first move on taking on the Gardens was to capitalise on the long-standing royal connection, which had endured through the lives of three separate Princes of Wales. The partners approached King George IV to request a license to use 'Royal' in the title of the Gardens, and the king agreed. The 'Royal Gardens, Vauxhall' was its unvarying title from that time, used on everything from spectacular posters to the brass buttons on the waiters' livery. Thomas Bish resigned from the management partnership in 1825, leaving Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes to manage Vauxhall on their own. In this, they were remarkably successful for a while, seeing record attendances in several seasons, and huge profits. However, they appear to have over-invested recklessly both in the Gardens and in their other businesses, and in 1840 they were declared bankrupt. This left the property in the hands of trustees for the next eighteen years, during which several lessees came and went, with varying degrees of success. It was increasingly hard to reverse the inevitable desertion of customers, attracted away in ever larger numbers by the newer and more sophisticated entertainments offered by music-halls and seaside piers. It was also becoming ever harder to attract effective managers, and to resist the tide of development of an expanding London,[34] which was itself inflating property values exponentially, finally making Vauxhall more profitable as building land than as a visitor attraction. After several false alarms, Vauxhall Gardens did finally close for ever after the evening of 25 July 1859. Anticipating its end, the developers had already moved in and acquired the site earlier that month, cleverly disenfranchising it from the Duchy of Cornwall for a consideration of £5,000, and turning it into prime freehold building land capable of accommodating three hundred new houses.[35]

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens should not be confused with the nearby Vauxhall Park, a scheme masterminded by Octavia Hill, which opened in 1890, in memory of Henry Fawcett, Liberal MP from 1865 and Postmaster General, who lived locally. Vauxhall Park is at the junction of South Lambeth Road and Fentiman Road. Vauxhall Gardens, a few minutes' walk to its north, is adjacent to Vauxhall Railway Station and Kennington Lane. All trace of Vauxhall Gardens itself, whether above or below ground, was obliterated during the demolition of 1859, and the subsequent re-development of the land. In the 1970s, the houses that had covered the site of the gardens for a century, cheaply built, badly war-damaged, and suffering from long neglect, were demolished in the slum-clearances. The Government was encouraging the creation of inner-city parks, so the dozen acres that had been Vauxhall Gardens were once more cleared and grassed over by the new owner, the London Borough of Lambeth, in an act of enlightened altruism. The resulting park, first opened to the public on 9 October 1976, was originally called Spring Garden, but in 2012, after a campaign by the Friends of Vauxhall Spring Gardens, was re-named Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, and a new monumental entrance to the park was created by local architects DSDHA near the site of the old Coach Entrance to the gardens on Kennington Lane. This entrance is adjacent to the Victorian pub called the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, which, since the 1940s, has become an iconic gay venue, and a training-ground for comedians and cabaret artists; designed by James Edmeston, this was one of the first buildings on the site after the Gardens closed in 1859, and it may contain elements of original Vauxhall Gardens buildings, notably several cast-iron columns, in its structure. Its significant role in the modern entertainment industry has, for many years, been the only direct continuation and development on-site of the entertainments that formed such an integral part of the Vauxhall Gardens experience. Other solid relics of Vauxhall Gardens do survive elsewhere; the silver season tickets issued by Jonathan Tyers are some of the most appealing survivals in museums and private collections, but there are also more than a dozen of Francis Hayman's original supper-box paintings, of which the largest collection is now in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; a small collection of pottery mugs, plates and bowls used at the gardens in the 19th century is in the Museum of London; and a clutch of mementos is in the Cuming Museum (now permanently closed) in Walworth Road, including a waiter's button, a piece of the gilt-wood Rotunda chandelier, one of the glass 'bucket lamps', and an oil-stained fragment from an elm-tree, probably all removed at the end of the 'last night'. The triangle of ground formed by Tyers Street and St Oswald's Place at the eastern end of the site includes several significant buildings erected there soon after the Gardens closed. The church of St Peter, whose high altar stands on the site of Vauxhall's firework tower, was consecrated in 1864. It, and the school and other ancillary buildings around it, were designed by John Loughborough Pearson. The house next to the church, which used to be the rectory, is the oldest building surviving on the site, having been originally built for Margaret Tyers (1722-1806), the widow of Jonathan Tyers the younger, following his death in 1792. It was later occupied by George Stevens, the final manager of the Gardens, and is still sometimes called 'The Manager's House.' fig.17 Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens with part of the City Farm, looking west, May 2015; the railway line runs between the trees and the buildings Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens today (2015) is a pleasant inner-city park, with many deciduous trees; it has a city farm and allotment gardens at one end, and railway arches at the other (fig. 17). It is used for the benefit of the local community, and provides space for fairs, seasonal festivals, outdoor concerts, firework displays (figs. 18 & 19), and, for the first time in 2014-15, a winter skating rink.

fig.18 Fireworks at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in 2013

fig.19 The Lambeth Wind Orchestra performing in 2014 Visitor information about the history of the site is provided at the new entrance. In 2015, the 'Royal Bank of Canada Waterscape Garden' designed by Hugo Bugg (b. 1987), a gold-medal winner at the 2014 Chelsea Flower Show, was translocated to the site, on a piece of ground adjacent to the old Queen Anne pub (now the Tea House Theatre). In 2015 it featured in the new Chelsea Fringe Festival, forming a major part of the 'Vauxhall Missing Link Green Trail' which would join together the parks and open spaces of Vauxhall. Near the Waterscape Garden, as this article is being written, Charles Asprey's new Cabinet Gallery is being built on the foundations of the old Lord Clyde pub, at the north-east corner of the old Vauxhall Gardens site, a new polygonal building as a homage to the Vauxhall Orchestra (figs. 20 & 21). Together with the nearby studio of Damian Hirst, and the inevitable emulation that two such well-known names will produce, and its easy accessibility by public transport, it seems that Vauxhall is once again due to become a by-word for contemporary art.

fig.20 Three contemporary British artists on the site in 2000, at the Lord Clyde pub, demolished soon after, now about to be replaced by the Cabinet Gallery fig.21 The Cabinet Gallery during building works, April 2015 In the pedestrian railway arch between Vauxhall station and the Gardens, the so-called 'Vauxhall Cross Interchange Mural' (2003), the longest vitreous enamel mural in London, was commissioned by Transport for London; designed by Alan Rossiter of the Free Form Arts Trust of Hackney, it was made by Burnham Signs Ltd of Sydenham. Against a ground of pale and dark blue, it illustrates on one side the appearance of Vauxhall Gardens in the 18th and 19th centuries based on contemporary engravings and plans, overlaid with lines from an 18th century Vauxhall ballad describing the attractions of the place – 'Each Profession, ev'ry trade Here enjoy refreshing shade, Empty is the cobbler's stall, He's gone with tinker to Vauxhall, Here they drink, and there they cram, Chicken, pasty, beef and ham.' (fig. 22) The other side, more abstract, uses modern quotations about the Vauxhall area, and snippets of its history, between reminders of some well-known local industries - Royal Doulton pottery, Marmite, and, of course, the Vauxhall Iron Works which became Vauxhall Motors (fig. 23). Both murals are duplicated in the narrower pedestrian tunnel to the north of the main road, Kennington Lane. fig.22 The Vauxhall Cross Interchange Mural (2003), north side fig.23 The Vauxhall Cross Interchange Mural (2003), south side Vauxhall Gardens today is dominated by Vauxhall Cross, the imposing modern building designed by Terry Farrell for the offices of the Secret Intelligence Service MI6. Completed in 1994, this building (see fig. 17, extreme left) is not on the footprint of the Gardens, but occupies an old industrial riverside site adjacent to Vauxhall Stairs, where visitors to the gardens would be dropped off by their watermen after the river crossing, and from where they would walk the final few yards. It is still possible to access the river at this point – it is regularly used by the yellow amphibious vehicles, run by London Duck Tours which ferry tourists around London and the Thames. The other notable contemporary building adjacent to the site of Vauxhall Gardens is Arup Associate's remarkable Bus Station, completed in Spring 2005, and already under threat of demolition in 2015. Around the park are street and building names which refer back to Vauxhall Gardens in its heyday; Jonathan Street and Tyers Street commemorate the greatest of all Vauxhall's proprietors; Worgan Street was named for John Worgan, one of the earliest of the in-house composers, and in the 1930s Vauxhall Gardens Estate to the north and east of the site, many artists, singers, musicians and fictional characters associated with the gardens are remembered – the composer Thomas Arne, the painter Francis Hayman, Addison's creation Sir Roger de Coverley, Jos Sedley from Vanity Fair, the great 19th century Master of Ceremonies C. H. Simpson, the illumination designer Robert Duffell, and at least twelve singers including Daniel Arrowsmith, Sophia Baddeley, Maria Theresa Bland, John Braham, William Darley, and the tenor Russell Grover, the last voice ever to perform in the Vauxhall Orchestra. |

|

|

6. Endnotes to the main text |

| [1] Warwick Wroth and Arthur Edgar Wroth,The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century (London: Macmillan, 1896) |

| [2] Mollie Sands, The Eighteenth-Century Pleasure Gardens of Marylebone 1737-1777 (London, The Society for Theatre Research, 1987) |

| [3] Mollie Sands, Invitation to Ranelagh, 1742-1803, (London, John Westhouse, 1946) |

| [4] David Coke and Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History ((Published in London for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in Britsh Art by the Yale University Press, 2011) , p. 195 |

| [5] Sutherland Lyall, Rock Sets; the Astonishing Art of Rock Concert Design (London, Thames & Hudson, 1992), p. 72-95 |

| [6] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 50 |

| [7] E. S. de Beer [ed.], The Diary of John Evelyn [1620-1706] (London, Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 425 |

| [8] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 191-2 |

| [9] The Spectator, No. 383, 20 May 1712 |

| [10] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 41 |

| [11] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 24-26 |

| [12] Ralph Hyde [intro], The A to Z of Georgian London , London Topographical Society, no. 126 (London, 1982), p. 19 |

| [13] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 30 |

| [14] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 23 |

| [15] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 75. As far as I know, dogs appear in just two images of Vauxhall, in 1737 and 1838 |

| [16] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 20-23 |

| [17] Emily Cockayne, Hubbub; Filth, Noise & Stench in England, 1600-1770 (New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2007) |

| [18] Thomas Jefferson, Preamble to the US Declaration of Independence, 1776 |

| [19] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 46 |

| [20] David Coke, 'Patriotism and Pleasure' in History Today, 62/5, May 2012, pp. 36-43 |

| [21] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 55-57, fig. 34 |

| [22] Coke and Borg 2011, p. 155 |

| [23] Jacob Simon [ed.], Handel, A Celebration of his Life and Times 1685-1759 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1985), pp. 212-213 |

| [24] Christopher Hogwood [intro], Thomas Augustine Arne, Lyric Harmony (Tunbridge Wells: Richard Macnutt, 1985) |

| [25] David Coke, 'Roubiliac's Handel for Vauxhall Gardens: a sculpture in context' in Sculpture Journal 16/2, 2007 |

| [26] E. Harris, 'Handel's Accumulation of Wealth' in Handel Institute Newsletter 13/1, 2002, p. 4 |

| [27] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 196-202 |

| [28] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 202-205 |

| [29] Caro Howell [ed], The Triumph of Pleasure: Vauxhall Gardens 1729-1786, Exhibition catalogue (London: Foundling Museum, 2012) |

| [30] Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde - Fashionable Society in Georgian London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013) |

| [31] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 307-310 |

| [32] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 275-280 |

| [33] Gary Hicks, The First Adman - Thomas Bish and the Birth of Modern Advertising, (Brighton: Victorian Secrets Ltd., 2012) |

| [34] Coke and Borg 2011, pp. 356-360 'Why did Vauxhall close?' |

| [35] David Coke has contributed an article and timeline on the disposal and development of the site after Vauxhall Gardens closed to Visions of Vauxhall: 150 years of St. Peter's Church and the Community, edited by Tim Clifford, Rev. Alison Kennedy and others, published by the North Lambeth Parish, 2015, pp. 4-11 |

|

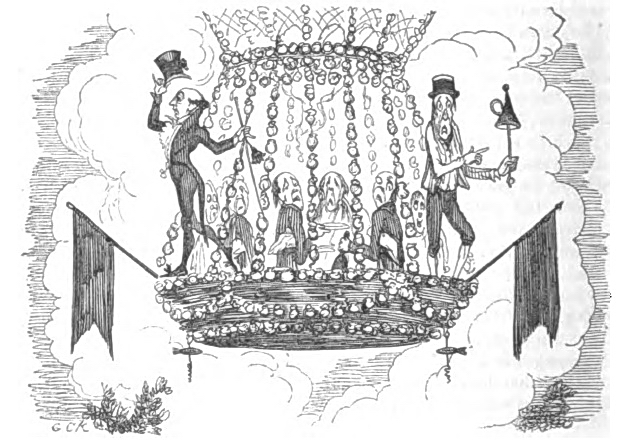

fig. 24 George Cruikshank 'The Last Night' with C.H. Simpson and the Vauxhall Hermit floating away in an illuminated balloon, with a party of woebegone waiters. |